January 30, 2024

Congress enacted EKRA, the Eliminating Kickbacks in Recovery Act of 2018, a law to fight patient brokering and recovery profiteering. EKRA prohibits accepting or paying kickbacks for referrals to recovery homes, clinical treatment facilities, or laboratories. As a result, EKRA promises to help stem the tide of opioid related fraud. Below, we explain how EKRA operates, how violations of EKRA may violate the False Claims Act. We also discuss the first prosecution under the law.

In late 2018, Congress enacted the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (the “SUPPORT Act”). Section 1822 contains the EKRA law, codified at 18 U.S.C. § 220.

Senators Marco Rubio and Amy Klobuchar originally sponsored the bill. EKRA targets patient brokers who improperly profit from attempts to help patients recover from addiction. Patient brokers recruit patients and shop them to the highest bidder. In addition, they frequently defraud patients and offer them bribes.

To fund the kickbacks paid to brokers, facilities and brokers push patients to expensive private insurance (often government subsidized). They may even pay insurance premiums for the duration of the treatment. Likewise, drug treatment urine drug testing is a multi-billion dollar a year business and so lucrative for treatment clinics, that they refer to it as Liquid Gold. As a result, facilities frequently over utilize expensive urine drug testing, and reap huge profits from the insurer.

The EKRA law operates by prohibiting any recovery home, clinical treatment facility, or laboratory from paying kickbacks to anyone. Notably, EKRA applies to all laboratories whether or not they perform substance abuse testing. For example, it would apply to a hospital laboratory that tests only hospital patients. Some have criticized EKRA for its expansive reach. However, no one argues that laboratories should pay kickbacks to secure referrals.

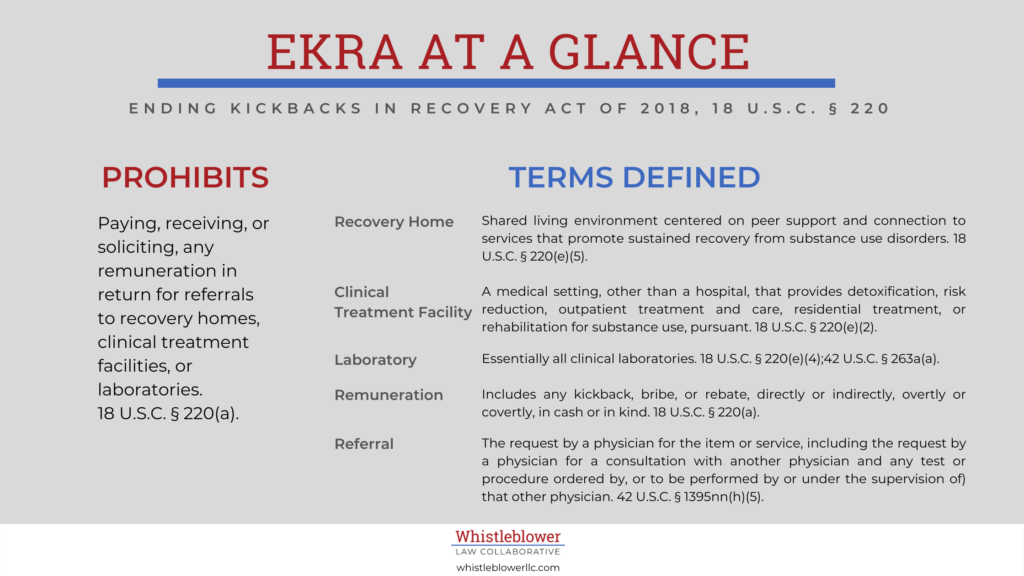

The Eliminating Kickbacks in Recovery Act prohibits anyone from paying, receiving, or soliciting, any remuneration in return for referrals to recovery homes, clinical treatment facilities, or laboratories.

In particular, the statutory text of EKRA provides that

whoever, with respect to services covered by a health care benefit program . . . knowingly and willfully-

(1) solicits or receives any remuneration (including any kickback, bribe, or rebate) directly or indirectly, overtly or covertly, in cash or in kind, in return for referring a patient or patronage to a recovery home, clinical treatment facility, or laboratory; or

(2) pays or offers any remuneration (including any kickback, bribe, or rebate) directly or indirectly, overtly or covertly, in cash or in kind-

(A) to induce a referral of an individual to a recovery home, clinical treatment facility, or laboratory; or

(B) in exchange for an individual using the services of that recovery home, clinical treatment facility, or laboratory,

shall be fined not more than $200,000, imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both, for each occurrence.

The EKRA law defines several of its terms, others are defined in similar anti-fraud law.

A shared living environment that is, or purports to be, free from alcohol and illicit drug use and centered on peer support and connection to services that promote sustained recovery from substance use disorders. 18 U.S.C. § 220(e)(5).

A medical setting, other than a hospital, that provides detoxification, risk reduction, outpatient treatment and care, residential treatment, or rehabilitation for substance use, pursuant to licensure or certification under State law. 18 U.S.C. § 220(e)(2).

A facility for the biological, microbiological, serological, chemical, immuno-hematological, hematological, biophysical, cytological, pathological, or other examination of materials derived from the human body for the purpose of providing information for the diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of any disease or impairment of, or the assessment of the health of, human beings. 18 U.S.C. § 220(e)(4);42 U.S.C. § 263a(a). Basically, this includes all laboratories.

Any public or private plan or contract, affecting commerce, under which any medical benefit, item, or service is provided to any individual, and includes any individual or entity who is providing a medical benefit, item, or service for which payment may be made under the plan or contract. 18 U.S.C. § 220(e)(3); 18 U.S.C. § 24(b).

Two terms are not defined, but similar to terms in the Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law and likely would have the same definitions.

Includes any kickback, bribe, or rebate, directly or indirectly, overtly or covertly, in cash or in kind. 18 U.S.C. § 220(a). It also includes the waiver of coinsurance and deductible amounts (or any part thereof), and transfers of items or services for free or for other than fair market value. 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a(i)(6). But it does not include copay waivers that are not advertised, and not made routinely. 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a(i)(6)(A). In addition, the term excludes certain other specified reductions and transfers of items made to increase access to care that carry low risk of harm. 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a(i)(6)(B)-(I).

The request by a physician for the item or service, including the request by a physician for a consultation with another physician (and any test or procedure ordered by, or to be performed by (or under the supervision of) that other physician). 42 U.S.C. § 1395nn(h)(5).

At first glance, EKRA seems similar to the Anti-Kickback Statute, 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b). The Anti-Kickback Statute also criminalizes kickbacks for with items and services covered by government health care programs. But there are key differences that make EKRA a unique and valuable tool when it applies.

The Anti-Kickback Statute applies only to items and services “for which payment may be made in whole or in part under a Federal health care program” 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)(1)(b). Because, Federal health care programs cover the vast majority of medical items and services, the Anti-Kickback Statute theoretically applies in almost all cases. However as a practical matter, the government is unlikely to prosecute cases that do not involve substantial government money.

The EKRA law eliminates that concern because it applies to any service covered by a health care benefit program. A health care benefit program is any public or private plan that provides medical services. Consequently, EKRA applies any time medical services are provided, whether the service is covered by government insurance, private insurance, or the patient pays herself.

Under EKRA, prosecutors can pursue all recovery-related kickbacks and bribes, not just those that threaten to directly damage the public fisc.

The Anti-Kickback Statute criminalizes almost all payment of money in exchange for referrals. It then excepts specific permitted relationships in safe-harbors. The Anti-Kickback Statute has eleven statutory and thirty-four regulatory safe harbors (many of which overlap).

In contrast, the EKRA statute defines seven statutory safe harbors and no regulatory safe harbors:

The Anti-Kickback Statute safe-harbor for employees is very broad and exempts nearly all payments to bona fide employees. The EKRA employee safe-harbor, on the other hand, only applies to payments that do not vary with the volume of referrals. Thus, under EKRA, covered entities may not pay their employees on a commission basis.

However, the EKRA copay waiver exemption permits a broad range of copay waivers, not just those that are offered for reasons of financial need.

Anti-Kickback Statute penalties include imprisonment of up to 10 years and a $100,000 fine per violation. But, a given case may include hundreds or thousands of individual payments and referrals. However, EKRA penalties are even more stringent. They include imprisonment of up to 20 years and a $200,000 fine per violation.

In January 2020, the Department of Justice announced what is believed to be its first conviction under EKRA. This conviction relates to the type of bribes that likely would have been covered by the Anti-Kickback Statute. Here, the defendant, a manager of a substance abuse treatment facility, solicited kickbacks from a urine drug testing lab.

The target of the prosecution was an office manager of a substance abuse treatment clinic in Kentucky. The individual admitted to soliciting kickbacks from the CEO of a urine drug testing lab in exchange for the clinic’s business. These bribes included a $4,000 check that the individual subsequently lied to investigators about.

Notably, DOJ’s press release does not address any prosecution of the urine drug testing laboratory. We expect that DOJ will continue to pursue that entity, however.

To date there have been only a handful of court decisions on the scope of EKRA. In 2021, a Hawaii district court concluded that EKRA did not apply to marketers. The case, Graves v. S&G, a civil employment suit, involved the lab terminating a marketing contract because it was illegal under EKRA. The Hawaii court’s ruling that EKRA did not extend to marketers was in direct contravention of the statute’s core statutory text and purpose.

In 2022 a different district court in California rejected the findings in the Graves v. S&G case that EKRA did not cover marketers. In US v. Schena, a criminal case, the California district court denied the defendant’s request to dismiss the EKRA charges and found that defendant’s scheme “to influence marketers by paying them illegal kickbacks to induce the referral of patients” was unlawful under EKRA. The California court found that whether the marketers were paid to recruit patients directly, or were paid to recruit patients through physicians, was “irrelevant,” as either arrangement was illegal under EKRA.

Following a trial, the jury found Mr. Schena guilty of violating EKRA, and other charges. In 2023, Mr. Schena was sentenced to 8 years in federal prison and ordered to pay more than $24 million in restitution.

The results in the Schena case provide an important example of the activities – such as recovery profiteering and body brokering – which ERKA was enacted to prevent. It should also act as a warning of the potential consequences individuals and companies may face for violating EKRA.

We have previously explained how the Anti-Kickback Statute can subject an entity to liability under the False Claims Act. When an entity submits a claim to the government, it promises that follows all of the federal health care law including the Anti-Kickback statute. In False Claims Act jargon, this is called implied certification theory. Health care providers make these certifications when they join government health programs or submit claims. In addition, the law states that claims resulting from a violation of the Anti-Kickback Statute are false or fraudulent claim for purposes of the False Claims Act. 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g).

Under Supreme Court guidance, a provider violates the False Claims Act every time he submits claims while failing to tell the government about violating the law if he knows that the violation is material. In other words, would matter to the government’s decision to pay. Thus, EKRA is very similar to the AKS and clearly important to Congress. Thus, a violation would likely provide a basis for FCA liability.

As a practical matter, the Anti-Kickback Statute will be in play any time EKRA applies to a case with significant government money. But there may well be cases where the narrowed EKRA safe harbors would make that the preferred vehicle for liability.

We will continue to watch the evolution of this law. We expect it will play a significant role in reducing addiction related fraud.