February 18, 2021

One of the more astute things I learned from an experienced lawyer as I was coming out of law school three and a half decades ago was this: It’s much more interesting and revealing to look at what people are doing five to ten years after graduation than what they do right out of the gate. What he meant was that people’s first choices often reflect how much debt they’re trying to pay off, or a first poorly-informed guess at what will work for them in a profession with many different avenues to pursue. Give it a decade, he was saying, and people will start to reveal themselves, their preferences, and their potential.

This observation has proven itself true more times than I can count.

Some of my law school classmates (many of whom I didn’t know at the time because of the size of the class) have gone on to fame, fortune, and all manner of impressive careers. I have watched in admiration as members of our class have achieved towering success in politics, in academics, and in the judiciary. We all take pride in how they have applied their legal training and what they have accomplished in their chosen fields.

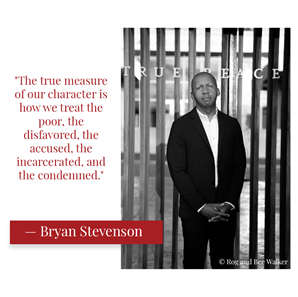

And then, in a class by himself, is Bryan Stevenson.

Coming out of a top tier law school, Bryan Stevenson could have pretty much written his ticket into any law firm job he wanted anywhere in the country. But he had other things in mind. He was determined to do something meaningful with his law degree – and unlike most of the rest of us – not mess around with training grounds or money making before getting right to it. No stop at a high-paying law firm; no learning at the heels of senior lawyers. No, Bryan went straight to the Deep South to work on death penalty cases. Alone. With no funding. No infrastructure to support him. No safety net. Gutsy? Crazy? Both?

Over time, he would expose the deep structural racial bias in the criminal justice system, proving the innocence of the wrongly convicted in case after case. He earned the release of capital convicts who had been wrongly imprisoned and placed on death row for years — in some cases for decades. He would argue the case before the Supreme Court that would lead to the abolishment of the death penalty for minors.

He also would found the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama. He would document and memorialize the hundred year terror of lynchings in the South. He would be honored with a MacArthur “genius” grant. His Ted Talk would go viral. He would write a book called Just Mercy that would be turned into a movie. He would become one of the most sought-after speakers in the country.

I wish I had known him before he became famous, back when I was just a law student trying to figure out what to do with my life.

Our paths would eventually cross, but just briefly. I am a proud supporter of his organization, and I marvel at what it has accomplished, against terrible odds. But most of all I am left speechless by the enormity of his contribution to this world, by what one talented and passionate person can accomplish with perseverance and a large dose of courage.

As our nation celebrates Black History Month, and as we reflect on the life stories that have truly inspired us, I wanted to express my admiration for, and gratitude to, my long ago classmate Bryan Stevenson.